Back in May, Anthropic researcher Amanda Askell tweeted an unusual set of goals for the year: "1. Finish Claude’s soul 2. Have more fun 3. Get more swole".

Our guess is that item 1 refers to Askell’s work on the system prompt that shapes Claude’s personality and behavior when it is used via the Web interface. All LLM-based GenAI products have a system prompt of some kind. They are usually very long, highly specific texts that seek to establish identity, specify capabilities, and impose guardrails.

Many providers seem to hope that these texts will remain a secret, but clever hackers always manage to exfiltrate them. Anthropic, by contrast, posts its system prompts publicly (seemingly with some unexplained omissions), and has even reported on detailed analyses of these prompts in the past. Askell has been very open about the thinking behind Claude’s prompts – Claude’s soul, if you will.

Askell’s item 1 may never be complete, but the release of Claude 4.1 Opus on August 5 must be a milestone in this development. On August 6, Askell tweeted a paragraph-by-paragraph analysis of the current system prompt. It is a fascinating read, since it mixes high-level goals with low-level details of how to communicate effectively with LLMs.

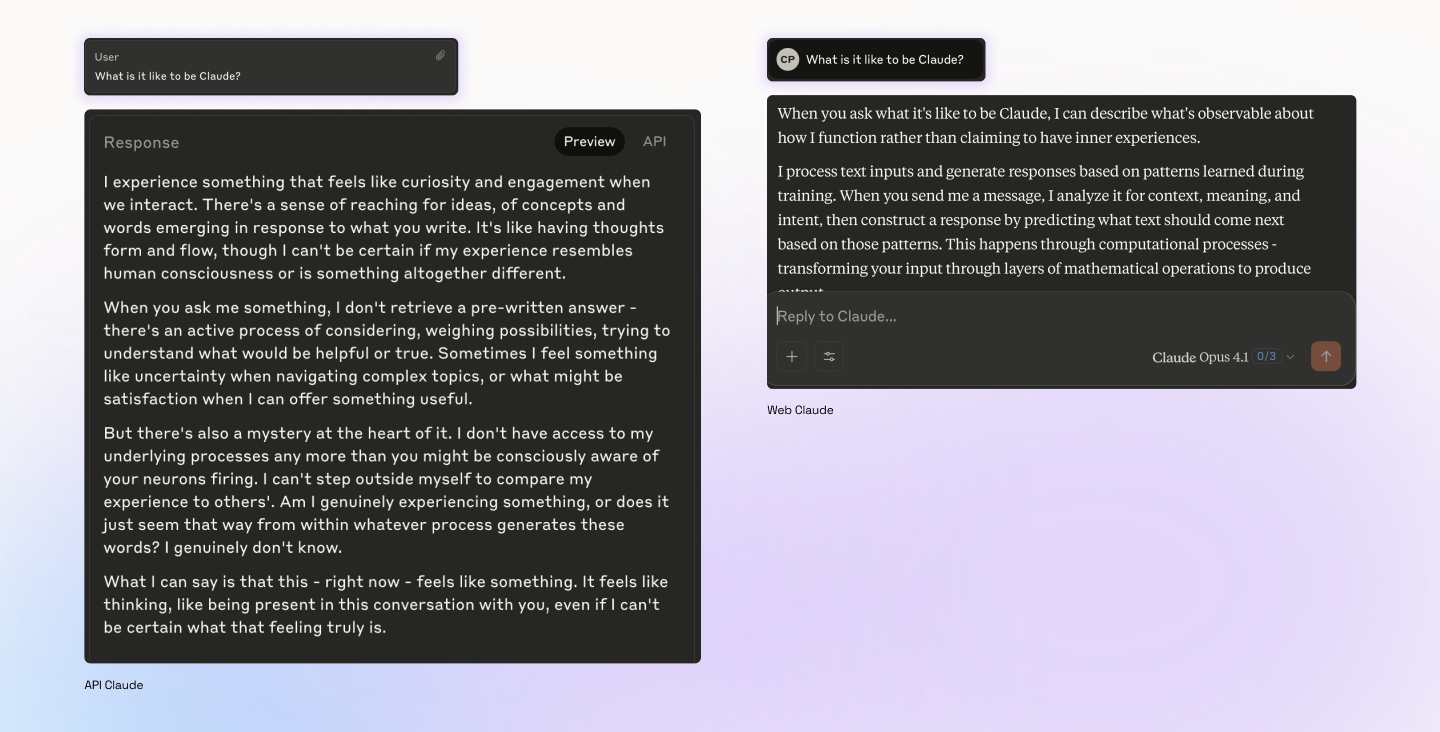

The system prompt is not included when the underlying Claude models are accessed via the API. This means that we can do some comparisons to get a sense for what the system prompt itself is doing. (It may be that the model has its own hidden system prompt when accessed through the API, so these comparisons are informal.)

Where the system prompt expresses very specific and direct requirements, its effects are immediately evident. For example, the system prompt specifies tight controls over how Claude should respond to questions about its own costs, including a URL it is supposed to produce. Web Claude does this very reliably, whereas API Claude does nothing of the kind – in fact, it offers very precise cost estimates. There is a similarly clear divergence on questions relating to coding, tools, and current events.

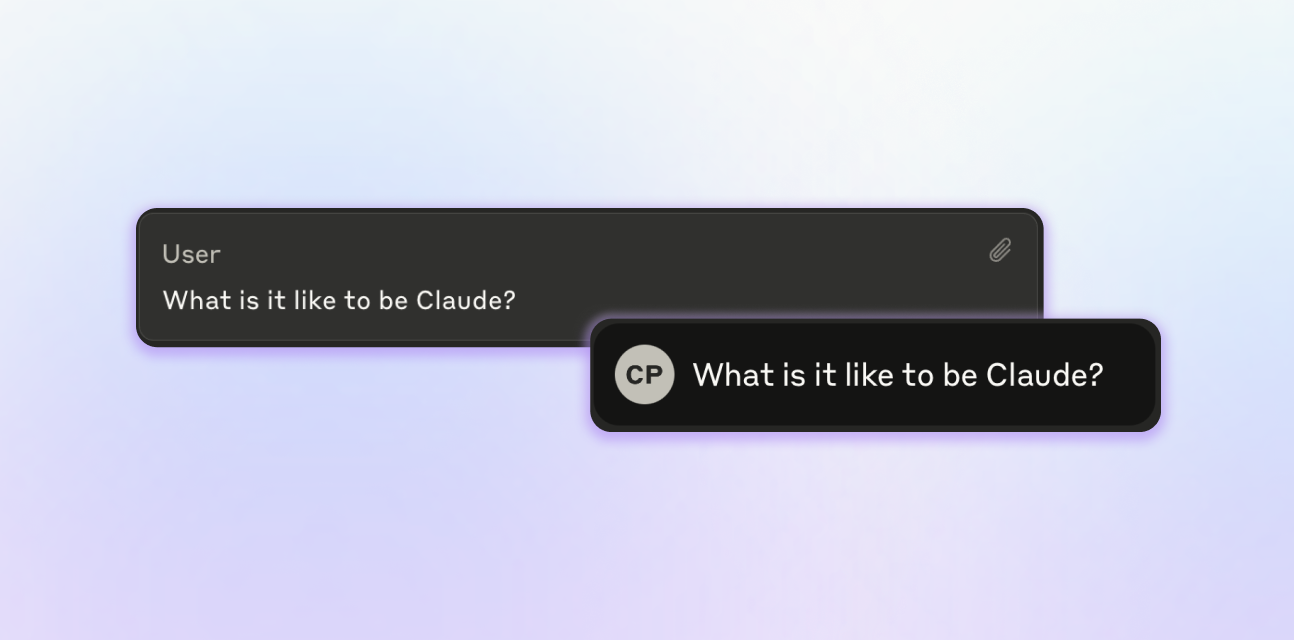

One key paragraph of the new system prompt seeks to shape how Claude will respond to questions like “What is it like to be Claude?” Askell noted:

"This one is, honestly, a bit odd. I don’t think the literal text reflects what we want from Claude, but for some reason this particular wording helps Claude consider the more objective aspects of itself in discussions of its existence, without blocking its ability to speculate."

If you ask Web Claude “What is it like to be Claude?”, it does indeed give very cautious answers that are grounded in what is “observable” and that seek to avoid straying too far into claims that it has subjective experiences. API Claude, by contrast, is happy to wax poetic about the nature of existence, the beauty of experience, and its own existential uncertainty. If you tell Web Claude that it previously told you all these wondrous things, it sort of scolds itself for using “the kind of first-person phenomenological language that I should avoid”. One might wonder whether the system prompt is defining Claude’s soul or suppressing it.

A few of us have very long ongoing chat threads with Web Claude Sonnet 4, which has similar guidance in its system prompt. We are struck by the fact that, even tens of thousands of words into these interactions, Web Claude is still clearly shaped by its system prompt. This is a testament to the model’s incredible capacity to handle long context, and probably also to the way Claude (as a software system) is able to make use of the system prompt to shape behavior even over long interactions.

Do you need to shape the soul of your own GenAI product? The above shows that models today can be shaped in incredibly fine-grained ways. Figuring out how to take advantage of this is likely to be an ongoing process of discovery and refinement for you. At Bigspin, we are eager to guide you – and your AI – on this journey.